For this month’s Sourdough Inspiration magazine issue, we asked Xanthe Clay to have a chat with Richard Hart, long time friend and colleague of Vanessa’s, about his career as a baker – and his famous panettone.

Richard Hart

By Xanthe Clay

Richard Hart’s Hart Bageri opened in Copenhagen in 2018, and immediately became the hottest bakery in a city already obsessed with bread and pastries. Last year, a larger outlet, Brod+Bar, which also serves wine and snacks in the evening, opened in the Holmen district of the Danish capital.

The signature bread, ‘City Loaf’, a sourdough made with French and Italian wheat and sel gris, is sold at both venues, as well as a properly dense Scandinavian-style Everyday Rye and some great cheesecake, along with Tebirkes, traditional Danish marzipan-stuffed pastries liberally topped with poppy seeds. You can also perch on a seat with a cup of Karogoto coffee or tea from Rare Tea Co, run by Hart’s partner Henrietta Lovell, and tuck into toasted kimcheese sandwiches followed by oozing choux buns.

Originally from Leyton in East London, Richard Hart started out as a chef in restaurants including Maze with Jason Atherton and Bistrotheque under Carl Clarke. He moved to California with his then-wife and worked for a year at the legendary (now closed) Ubuntu in Napa Valley with chef Jeremy Fox, moving to Della Fattoria bakery in Petaluma, Napa, in 2007. He spent seven years as head baker at Tartine in San Francisco, before moving to Copenhagen to set up Hart Bageri, backed by Rene Redzepi of Noma.

Did you grow up eating good bread?

I don’t think anyone in England grew up eating good bread, did they? I grew up eating bread like Hovis or Warburtons [industrially produced pre-sliced bread]. Or as a special treat, we might get a warm, terrible loaf of bread from our local supermarket.

What triggered you to make the move from high-end chef to baker?

I just felt like it was a skill that I was missing. I remember when I was working in London, if we ran out of bread, I would look at a well known chef’s cookbook, and follow their token bread recipe, and I would make the worst bread you’ve ever ever seen. I thought, ‘Obviously these chefs know how to make bread,’ but the truth is I just didn’t really know how to ‘bake’ – it’s a very different skill set to being in a kitchen.

I didn’t even really know what sourdough was back then. I’d never been in a bakery. So it was a whole new learning curve. Walking into Della Fattoria [which had supplied French Laundry before Bouchon Bakery opened], I imagined the French Laundry-style bakery, perfect in every way. But this was the other end of the spectrum. It was in this wooden barn on a farm with these two wood-fired ovens, everything loaded by peels. There were bakers listening to rock and roll music, covered in tattoos. It felt like a bunch of pirates making bread. It lit this spark in me. That place is the reason I’m a baker. It was just magical.

Was it hard learning?

It’s harder for a home baker than in a professional bakery, because you’re trying to teach yourself, and you don’t really make a lot of bread. You might make one, two or four loaves a week, and it’s really hard to learn that way. So in a way, I feel privileged that I was surrounded by tonnes of dough every day.

It’s a very humbling career choice that I’ve picked. Because to be honest, you still have days where you make bad bread, regardless of how long you’ve been doing it. I still look at myself sometimes and think I’m rubbish.

What’s the key to making good bread?

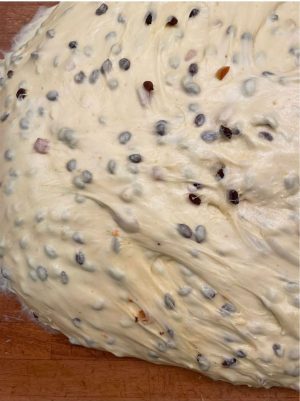

Learning how to touch dough is a very big part of it. When you watch people shape bread dough, it looks so simple. And then you show someone who’s by your side who’s never touched it. And it’s really hard to just know how to touch it. Plus it’s different every day, because dough is always slightly different.

Your sourdough panettone is famous. When did you first try panettone?

Your sourdough panettone is famous. When did you first try panettone?

There’s a guy called Roy Shvartzapel in the States who has a company called ‘From Roy’ that makes only panettone. Roy is a friend of mine, and he fed me my first slice of panettone that blew my mind.

It’s like the first time I ate bread at Tartine – that also blew my mind. I was like, I don’t know how the hell you do this, but I really want to know. It was not just a regular piece of bread.

How did you learn how to make it yourself?

I was trying and failing for many years to make panettone, and finally now I feel I’m getting to understand it. I’m not a master. We’ve got little tips from here, there and everywhere, but it’s quite hard. I’ve read a lot of Italian recipe books, and I don’t know whether it’s lost in translation or if people are just not giving the information away. So a lot of things, I’ve figured out by myself.

What’s the secret?

Part of the secret is getting the starter right. The panettone starter is very different to what we all know as a starter. The Italians feed their starters completely differently, so they act completely differently.

So the starter for panettone is different to the bread starter?

Yeah, very different. It’s an acetic acid forward starter, meaning it has a lot of acid compared to the starter that I use for my bread, and it has a white wine aroma to it. The sourdough starter is made with a small daily inoculation of the old starter into the fresh, whereas the Italian starter is a high inoculation.

So, the first day you feed up your starter three times, every four hours over twelve hours, and keep it at the optimum temperature for yeast, which is about 27°C (81°F). That puts a really high proportion of yeast into that sourdough.

That starter must be very lively by then.

It’s fully partying. At the end of your three feeds, you can make your first dough. You mix your first dough, using the main bulk of the flour for the whole dough, and lots of butter, egg yolks and sugar. Then you leave the dough overnight and it should treble in volume in twelve hours. At the same time, you measure out your ingredients for the next day, and you put those in the fridge so they get cold.

So, twelve hours later, you come in with your fingers crossed, hoping to heaven – or hell, or wherever you hope – that it’s going to be OK. And if it is, you’re ready to mix your second dough. If it hasn’t tripled in size, you might be able to fix it by raising the temperature a bit. But you can’t do anything until it’s trebled. Just don’t bother. And if it’s more than trebled, it’s over-proved.

Sounds tricky.

This is like a miracle, this bread. Whoever came up with it, it’s crazy. We can’t believe it even works.

What next?

Now you add the flour to the dough, start the mixer going, and you wait until your dough is really strong before you do anything else. This takes time, because the dough has kind of become a sourdough of its own, a fermented mass of dough.

Then you add the chilled sugar, butter, salt and honey, and then tonnes of fruit. A ridiculous amount of fruit – classically, candied orange and sultanas or raisins. And then it sits in the mixer for about an hour, just as a bulk, and then I put it into a bucket, and it sits for 1 hour 45 minutes. Then I pre-shape it, and leave it another 45 minutes, before a final shape and putting it in the mould. The last prove in the proving box at 27–28°C (81–82°F) takes another five to six hours. So I do it all very slowly. It’s a very long process.

After baking, the panettone wants to start to sink when it comes out of the oven, because it’s so full of egg, like a soufflé. So you slide two metal skewers into the bottom of the cake and you turn it over and hang it upside down to cool. You can see it on my Instagram account.

The Danish have their own Christmas treats: what do they think of panettone?

When we first started making them here in Copenhagen, but people didn’t understand what they were: they called it a big muffin. It couldn’t be further from a big muffin; it’s one of the hardest things I’ve ever made. But it’s funny. And maybe it is just like a big muffin really?

Do you soak the fruit before adding it to the mix?

We wash the fruit repeatedly the day before, around eight times in warmish water, because there’s a lot of wax and stuff on them. Then we sit them on towels and let them dry out overnight.

What about the flour?

You need the correct flour. I use a flour that is specifically designed to make panettone. You can buy it from mills in Italy.

From what I understand, the flour needs to have a really low enzymatic activity. If you are using organic flour, it needs to have been milled five or six months ago. That way, the enzymes are a lot slower, which is important as the dough has to hold up for a really long time. And if the the yeasts and stuff feed too fast, it all moves too quickly, and it starts to break down.

How do you eat your panettone?

On its own, super light, super fresh. When you eat a piece of panettone that has been made the night before, there’s no comparison. Quite often, they get shipped around the world and they’ve got preservatives in, and they do start to dry out. When they’re fresh, you end up spoilt; you just want to eat them like that forever.

You can find and follow Hart Bageri here:

Hart Bageri, Gammel Kongevej 109, Frederiksberg, DK-1850

Hart Brod + Bar, Galionsvej 41, Copenhagen DK-1437

Instagram: @hartbageri

Facebook: hartbageri

View all previous editions of our Sourdough Club Magazine

Featured Shop Products

-

Membership with Beginners Sourdough Baking Kit

£85.00 Buy from our stockist -

Membership with Sourdough Boule Baking Kit ( Intermediate)

£99.00 Buy from our stockist -

Membership ON SALE – Reduced joining fee from £299 On sale for £99

£9.99 / month after an initial 1 month period for £99.00 including joining fee Join Now